This, in the end, all features and properties of a typeface predetermine what is possible in the other components of a typographic product:

- The repertoire of glyphs can limit what can be written with a specific typeface.

- The number of OpenType features can hinder or facilitate the use of many editing conventions.

- Finally, basic parameters such as kerning, the x-height and the width of the normal interword space can make the work of the editorial designer — and the reader — a joy or something not so pleasurable.

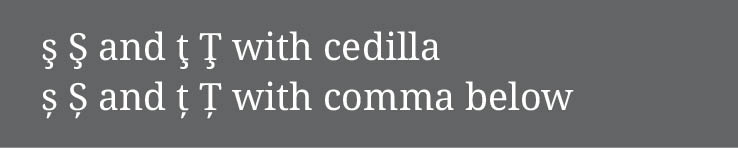

One of the key attributes of the font format — namely and de facto OpenType — is that it allows localizations, that is, script-specific rules. For Romanian writers, for instance (fig. 1), t and s with cedilla (and its uppercase counterparts) can be properly rendered as t and s with comma below when the typeface is Romanian-compliant. In Catalan (fig. 2), instead of an unmodified geminated el (l·l), we can have a properly compensated ligature.

As for features, any typeface, to be made public nowadays, should have the following two:

Four modes of figures.

Not only do we need modern and old-style figures, but both with variable and fixed width as well. Not to forget the choice of the default mode, which can be unreluctantly old-style when the typeface is roman and suitable for long-running text.

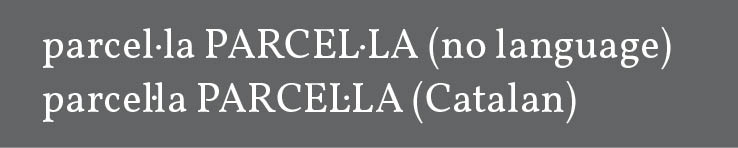

All caps and all small caps modes.

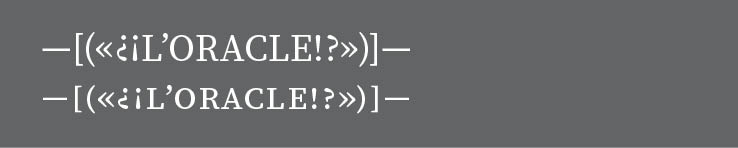

When using these features, all figures and all punctuation marks must be vertically aligned according to the immediate context, be that uppercase or small caps (fig. 3). Additionally, double and single quotes (which include the apostrophe) are glyphs typically aligned to go with lowercase ascenders and need to be lowered when the mode in use is all small caps. Let us not forget that capital eszett (ẞ) must be available as a glyph in small-cap shape.

Now let’s take a turn and look at the repertoire of glyphs:

Superindex and subindex.

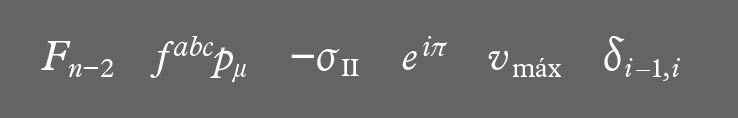

Typefaces ought to go beyond 0–9 figures and include in these two features glyphs such as the following (fig. 4):

- Basic mathematical operators: plus, minus, multiplication, equal, tilde, less-than, greather-than.

- Some punctuation marks: parentheses, comma, full stop, semicolon, slash (also called solidus).

- All lowercase and uppercase roman (or latin) letters, even those with diacritics.

- All lowercase and uppercase greek letters.

Ligatures.

Please, do not design ligatures that do not improve the visual perception of the glyph group.

Other characters.

Here are some other needed glyphs:

- minus (2212)

- two-em dash (2E3A)

- three-em dash (2E3B)

- horizontal bar (2015)

- double vertical line (2016)

- dot operator (22c5)

- empty set (2205)

- swung dash (2053)

- interrobang (203D)

- capital eszett (1E9E)

- right pointing index, white and black (261E, 261B)

- triangular bullet (2023)

- hyphen bullet (2043)

- black bullet, leftwards and rightwards (204C, 204D)

- rightwards arrow, normal and heavy (2192, 2799)

- dotted circle (25CC)

- half bracket in top left, top right, bottom left and bottom right positions (2E22, 2E23, 2E24, 2E25)

Conspicuously, thus, well-prepared fonts cannot be light-weight files. In addition to more glyphs, good fonts require extensive coverage of kerning pairs, and this means more lines of code. Taking into account all that I pointed out (and obviously left out), one can see why a typeface design project can never be short-lived. Typefaces are a lot of work, but fascinating nonetheless.